Security Council Open Debate: Sexual Violence in Conflict, April 2019

Sexual Violence in Conflict: Rooted in gender inequality and structural violence

by Zarin Hamid and Sarah Werner, WILPF Women, Peace and Security Programme

SUMMARY

Accountability and a survivor-centred approach to addressing the root causes and detrimental effects of sexual violence in conflict were front and center during the 23 April 2019 United Nations Security Council Open Debate on Sexual Violence in Conflict (SVIC). This Open Debate on the Secretary-General’s tenth annual report on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) is held annually at the Security Council. This year 83 Member States and Regional Groups made statements. Briefers included UN Secretary-General (UN SG) António Guterres, the Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict (SRSG) Pramila Patten, 2018 Nobel Peace Prize Laureates Denis Mukwege Mukengere and Nadia Murad, human rights lawyer, Amal Clooney, and Inas Miloud, co-founder and Director of the Tamazight Women’s Movement in Libya.

Resolution 2467

Presiding over the Security Council for the month of April, Germany led diplomatic efforts for a Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) resolution aiming to include a new mechanism (a formal Working Group of the Security Council). However, this mechanism was removed from the final text. With 13 out of 15 votes in favour, with China and Russia in abstention, the Resolution in its final form passed the Security Council as UNSCR 2467.

The negotiations over the Resolution were fraught. German civil society who work with front-line defenders came out with a public statement in advance of the debate arguing that if pre-negotiation discussions suggested a resolution would weaken the WPS agenda, it should not be introduced in the Council. Despite this and concerns about undermining of women’s rights, the Resolution was pushed forward and adopted.

The most difficult issues in the negotiations were language on whether to establish a mechanism (i.e. a formal working group of the UN Security Council) on sexual violence in conflict and on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of victims of sexual violence. It is understood that concerns were raised about a formal mechanism by several actors and groups. During negotiation, States, in particular, Russia, China, and the US opposed the mechanism, so therefore no new working group was established. In the final stages, the US proposed compromise language to proposed language on SRHR, but the final text ended up making no direct reference to SRHR. Although this leaves languge in SCR2106 OP19 as precedent language, the absense of this committment in the context of growing attacks on women's rights indeed still sets a bad precedent. Following the passage of the resolution, France, Belgium, South Africa, and the United Kingdom spoke about the importance of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) for survivors.

The Resolution asks for a gap assessment and recommendations by the Secretary-General in his next report (2020). The language noted “within existing resources” (OP5). It is essential that survivors, women-led civil society, service providers are part of the design of this assessment. The text also references that sexual violence should continue to be addressed in the Informal Expert Group (IEG) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) (OP4) and this requires deepening of the work on WPS in UN country teams and across the UN system. The Security Council also requested the Secretary-General to report by end of 2021 to the Security Council on women and girls who become pregnant as a result of sexual violence in armed conflict, including those who choose to become mothers, and children born of rape (OP 18).

The Resolution’s introduction of new language on a survivor-centred approach calls for prevention and response to be non-discriminatory and specific and to respect the rights and needs of survivors, including vulnerable or targeted groups (OP16). This creates an opportunity for women-led civil society, along with existing tools, to demand the increased role of human rights institutions and action at the national level. Despite previous iterations, the final text did not explicitly mention key intersecting human rights issues facing victims and survivors of SVIC, including: sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), access to abortion, particularly after sexual violence has occured; and women human rights defenders (WHRDs) who are targeted during conflict. Moving forward to 2020 and the 20th Anniversary of UNSCR 1325, it will be important to remember that solutions that change local women’s lives require political will and concrete action, not further resolutions.

In framing the debate, briefers echoed one another in calling for the Security Council to act on its leadership prerogative, and lead the way to legally addressing crimes of SVIC, holding State and non-State actors alike accountable for ending impunity and providing reparations and other means of support to survivors. During the debate, discussions of a survivor-centred approach and debates over what this means, particularly energised support for sexual and reproductive health and rights within a context of global pushback on these issues, were notably salient.

SPEAKERS

The German statement to the Council underlined the importance of accountability for SVIC crimes, monitoring of information on non-compliance by mechanisms of the Security Council, responsiveness by sanctions committees against perpetrators of SVIC, and an overall employment of a survivor-centred approach to addressing sexual violence. Germany also highlighted gender inequality and women’s political, social, and economic “empowerment”, the need for a gender analysis to bolster prevention and participation, and emphasis on a survivor-centred approach to prevention, participation, service delivery, and justice and accountability as critical to the prevention of and path to addressing SVIC.

The UN Secretary-General António Guterres reminded the Council that there have been many efforts by UN bodies to address prevention and protection of people from SVIC, but governments need to do more to support survivors, such as sharing information to sanctions committees and in conducting security and justice sector reform. The Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict Pramila Patten stressed to the Council that survivors are not a homogenous group and they require services and measures of response appropriate to their context, including men and boys in the context of war and conflict, and LGBT who are particularly targeted. Furthermore, on the subject of accountability, Ms. Patten stated, “The reality is the implementation of resolutions commitments remains slow and criminal accountability remains elusive. Wars are still being fought on and over the bodies of women and girls. Sexual violence fuels conflict and severely affects peace. To turn the tide we must increase the cost for those who perpetrate and uphold a culture of accountability and not impunity.” In concluding her statement, Ms. Patten asked for additional targeted measures of accountability and justice for perpetrators, reparations for survivors as part of international law, and the Council’s due consideration for a survivor’s fund.

Speaking in her capacity as the chairperson of the Tamazight Women’s Movement, an organisation that is committed to intersectional feminist research and advocacy on indigenous issues in Libya, and on behalf of the NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security, of which WILPF is a founding member, Inas Miloud, called out the Secretary-General’s visit to Libya in not having included real engagement with real everyday Libyans, stressing that peace cannot be built without engagement of ordinary people. Ms. Miloud called for an end to the sale of arms that continue the conflict in Libya despite the UN arms embargo, and in a situation rife with violence at home and in the public space, protection for the human rights of migrants, WHRDs, and human rights defenders (HRDs), she enjoined the Council for critically needed specific measures to protect civilians.

Ms. Miloud stated that the work of women human rights defenders “remains essential for both protection of basic human rights and peace and security in Libya, as well as for providing life-saving services to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence such as food, medical care, and free counseling”. Recounting the rape of her friend in 2016, Ms. Miloud informed the Council that not only is sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) underreported due to stigma, fear of retaliation, and a lack of trust in the judicial system, indigenous women belonging to communities such as the Toubou, Tuareg, and the Amazigh are further targeted and marginalized due to systemic decades long discrimination against these communities. She pointed out to the Council that the Libyan WHRD, Amina Maghroubi, had traveled to the New York to the very same chamber “to deliver these same messages in 2012 and this should show you that your efforts to bring peace to Libya has not been enough”.

Echoing Ms. Miloud, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Nadia Murad reminded Member States, “We come to the UN and deliver statements, but there is no concrete action taken to address the issues facing the Yazidi community and women and girls”. She went on to remind them that Yazidi girls and women broke past the stigma of talking about SVIC, and told their stories to the world in the hope that it would bring justice and urge the international community to bring ISIS criminals to justice, but so far no one has been charged. She elaborated that while 80% of the Yazidi population in Iraq are in camps, there are thousands of ISIS elements who remain free or detained but without charge or trial. Ms. Murad called on the Council to act on behalf of survivors, statings “We want them to brought to justice, and they must be tried before a special court so that they see justice.” She assured that this would send a strong message to other perpetrators, and prevent acts of SVIC in the future.

Ms. Murad’s co-Laureate, Denis Mukwege, encouraged the Council “to act and bridge the gap between law and practice and create a better world free of SVIC”. Mr. Mukwege reminded Member States that survivors have a right to reparations, quality care, which should be considered a human rights action, and justice. He urged local organisations to be involved in early warning and data collection that can be used in evidence gathering for accountability measures and shared with sanctions committees, and for the international community to establish a survivor fund for programs and projects in countries that are failing to address their responsibilities.

Human rights lawyer and legal counsel to Nadia Murad, Amal Clooney briefed the Council on the cases against ISIS crimes against Yazidi women, and provided four options should they forgo the opportunity to hold perpetrators of SVIC accountable for their crimes. Framing her argument for justice and accountability alongside a peace and security lens, Ms. Clooney called for a substantive effort to investigate, charge, and prosecute ISIS fighters and leaders for the genocide against the Yazidi community before they are released from custody or before they “shave off their beards and go back to their normal lives”, and in particular for the crimes of SVIC against Yazidi women. Ms. Clooney called on the Council, which by even discussing SVIC in the Chamber are making the link between peace and security and SVIC, to recognize the opportunity at hand: thousands of ISIS members in custody, the UN Team is collecting evidence, survivors are waiting to testify and there are calls by people in the region for international trials. Should the Council choose not to hold ISIS accountable for its crimes, Ms. Clooney provided four alternative options, including the Security Council referring the matter to the International Criminal Court (ICC) as many survivors have called on; the setup of a special court by like minded states by treaty; referral of the matter to the EU with support from Member States; or Iraq can enter into a treaty with the UN to setup a hybrid court as was done in Sierra Leone.

Recalling the trials of Nazi criminals Ms. Clooney left the Security Council with a call to stand up for justice that will be heard resoundingly in posterity, telling Member States “This is your Nuremberg moment. Your chance to stand on the right side of history. You owe it to Nadia and the thousand of women and girls who must watch ISIS members have off their beards and go back to their normal lives while they the victims never can[...]”.

KEY THEMES

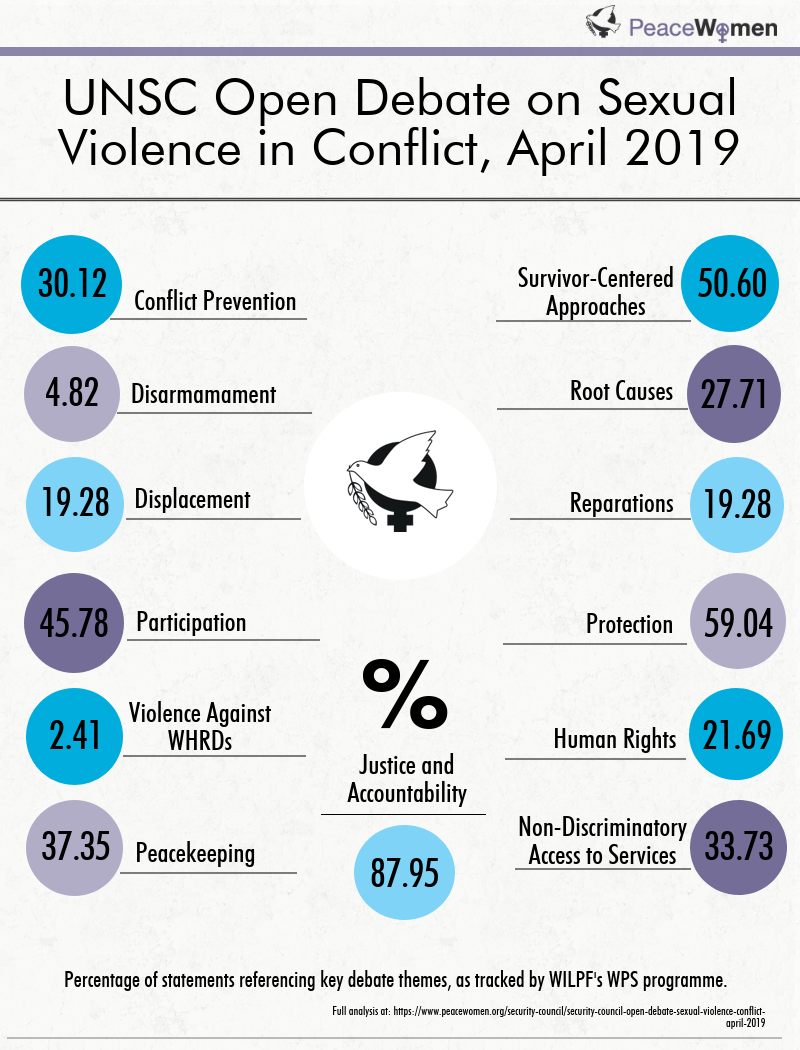

Protection, Prevention, Participation

Over 86% of Member States recalled the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda as the framework under which the international community must step forward in its efforts to answer to the issue of SVIC, including protection, protection, and prevention. Over 59% of Member States called on one another to bolster commitments to protection of civilians as part of international law. Answering the call for both protection and accountability, many Member States called for sexual violence in conflict to be a criteria used for designation of sanctions against perpetrators. Lamenting the watered down final text of UNSCR 2467, South Africa told the Council that while the initial draft text aimed at maximum protection of “victims” of SVIC and ensuring full accountability for related crimes, the final text discounts the large rights gains made in the benefit of all people. In its statement to the Council, Ghana outlined five areas of intervention on behalf of African Women’s Leader’s Network Group of Friends, in particular calling for primary focus in preventative efforts on structural and gender inequality, which are among the root causes of SVIC. States like Portugal and the Netherlands called for protection alongside reparations and access to legal action. Costa Rica was one Member State that linked the protection pillar to LGBT individuals who are affected by conflict, calling on States to establish robust legal frameworks with broadened scope that address gaps in existing protection efforts, so that they are inclusive of women, girls, and those in the LGBT population.

In many instances, statements by Member States linked accountability and justice as a prevention tool, rationalizing that when those guilty of SVIC are held investigated, prosecuted, and punished, future perpetrators will be deterred from similar heinous acts. States like Equatorial Guinea, Iran, and Hungary went a step further to remind their peers that the best prevention tool is to prevent conflict from occurring in the first place. Echoing Ghana in its call to attention on structural and gender inequality as root causes of SVIC, Hungary outlined that prevention starts in times of peace, where there is respect for women and men, rule of law, with women’s full and effective participation in society as the foundation of prevention. Resolution 2467 emphasizes that safety and empowerment of women and girls is important for their meaningful participation in peace processes, and that advancing gender equality and women’s political, social, and economic empowerment is critical to the prevention of and response to sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations.

During the debate, only 19 Member States and States groups (23%) made mention of the importance of including women meaningfully in peace processes. Statements by some Member States, such Kenya, Morocco, Sudan, India, and United Arab Emirates among others, called for increased participation of women at various levels of public life, including in peace processes, peacekeeping and security sector positions, the political arena, and in public service. Despite sexual and gender based violence rife against women in its borders, Pakistan took pride in its prominent contribution to peacekeeping as a leading troop contributor to the UN, and its planned deployment of an all female team in the Democratic Republic of Congo next month. WILPF stresses that adding women to miliarised institutions and processes is not meaningful participation. Instead, participation of women must be on all levels of ownership over their economic, social, political and civil rights.

Survivor-centred, victim-informed, and non-discriminatory access to services

Briefers like Inas Miloud and UN SRSG Pramila Patten, and over 50% of Member States welcomed the survivor-centred, victim-informed approach embodied in the Resolution text, with countries like Belgium highlighting LGBTI individuals who face multiple forms of discrimination; and South Africa advocating in this context for comprehensive, non-discriminatory services, sexual and reproductive health. Multiple states called out their regret that the agreed upon Resolution text does not respect the gains made with respect to inclusion of language on SRHR and LGBT issues in the context of SVIC. During the vote on the Resolution proposed by Germany, Canada and South Africa identified the proverbial elephant in the room, with South Africa stating that “text calls for survivor-centred approach, while denying survivors SRH when they need them most. Council is therefore telling survivors that consensus is more important than their needs”. Canada reminded the Member States that they “can’t promote gender equality and implementation of survivor-centred approach without SRHR” Belgium asked the Security Council to call on all Member States to provide comprehensive services that non discriminatory, including SRHR, legal, psychosocial, economic support; for Belgium this includes freedom of choice, access to safe abortions. This was in stark contrast to the US threat to veto the entire Resolution should SRHR is mentioned in the text. Moving forward, a holistic, survivor-centred approach must include appropriate multisectoral services for all survivors of sexual violence, such as clinical treatment of rape, medical, psychosocial and legal services, including comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care and rights such as access to emergency contraception, safe termination of pregnancy, and HIV prevention and treatment.

Root Causes

Gender inequality was underscored by 28% of Member States as the root cause for sexual violence in conflict, with states like Belgium, France, Ghana, Japan, Norway, and Vietnam warning that unless root causes are addressed, sexual violence in conflict will not be substantially addressed or prevented. While Member States chose not to go beyond mentioning gender inequality as a root cause of SVIC, WILPF calls your attention on the following: gender inequality exists because of patriarchal norms bolstered by structural violence that discriminates against women’s economic, social, civil and political rights. Resolution 2467 identifies root causes of SVIC specifically as structural gender inequality and discrimination, condemning violence, discrimination, and harassment against civil society, who the Resolution identifies as important to changing norms, and calls in OP 21 on States to “put in place measures to protect them and enable them to do their work”. Furthermore, the Secretary-General’s report articulates that while the UN approaches SVIC from an operational and technical perspectives, it “remains essential to recognize and tackle gender inequality as the root cause and driver of sexual violence, including in times of war and peace”. In order to honestly address root causes of why sexual violence in conflict occurs in the first place, it is critical to dissect the ways in which women’s human rights are denied, watered down, and criminalized around the world, in varying degrees in the home countries of these Member States.

Conflict Prevention

More than 50% of the Member States and Regional Groups’ statements acknowledged the use of sexual violence as a weapon and tactic of war, frequently employed within the context of a broader strategy. Though acknowledged less explicitly and often, the statements were also marked by a distinct increase in recognition of the link between conflict prevention and sexual violence. This year, 30% of states acknowledged the link directly. The most effective speakers to this theme were those that linked conflict prevention, sexual violence, root cause analysis, and calls to action. Equatorial Guinea’s remarks were a highlight in this regard, clearly asserting that “the most effective way of combating sexual violence in conflict is to prevent the conflict itself,” calling on parties “to commit to the protection of civilians” through acting in accordance with international law and General Assembly and Security Council resolutions, expressing concern “about the slow progress of eliminating sexual violence in war,” and the need for acknowledgment that the “root cause of violence and conflict is sexual violence.”

Displacement

Out of 83 Member States and Regional Groups making statements at the debate, 19% referenced displacement and humanitarian responses. Though limited in number, the references were quite strong. Several Member States, including Equatorial Guinea, the Dominican Republic, Belgium, Costa Rica, Malta, South Africa and Georgia, acknowledged sexual violence as a driver and result of displacement and sexual violence-driven displacement as part of a broader strategy and tactic of war. The African Union, Kuwait, Kazakhstan, France and Ireland, among others, recalled that displaced women and girls are at greater risk of and more heavily impacted by sexual violence. Nobel Laureate Nadia Murad, noting that 80% of Yazidi population in Iraq are in refugee camps, emphasized that survivors of sexual violence in displacement camps often face the same trauma to which they were initially subjected. As Ms. Patten underscored, survivors of sexual violence in conflict are not a homogenous group. Displaced survivors of sexual violence in conflict, and displaced women and girls that survive sexual violence within refugee camps, must have access to a wide range of services, especially health services, that meet their diverse needs. Jordan, which hosts 1.3 million refugees (many women and children), Bangladesh, and Nigeria applauded the role of civil society as partners specifically in the context of displacement and humanitarian response and called for their increased involvement.

Those Member States with significant refugee and internally displaced populations, including Jordan, Turkey, Bangladesh, and Nigeria, acknowledged the need to provide holistic services for and ensure the safety of displaced survivors of sexual violence, emphasized that governments should create peaceful conditions for return of displaced, especially through eliminating the culture of impunity for sexual violence that not only creates more refugees but also decreases the likelihood of survivors’ voluntary and safe return. Iraq has taken concrete steps in this regard. The President of Iraq, working with Nadia Murad, has drafted a bill for Yazidi survivors, which aims to provide all Yazidis with compensation, to guarantee them a dignified life, and to reintegrate them back into society. Concrete steps in this vein should be encouraged.

Reparations

Of note, 19% of Member States and Regional Groups’ statements included affirmations of the right of victims of sexual violence in conflict to reparations. This does not include references to establishments of survivors’ funds, which were mentioned separately and less frequently. Though the discussions were limited, these references represent a significant increase from previous years and indicate a degree of progress in advocacy work and analyses surrounding reparations. They are also a welcome contribution to expanding discussions of justice and accountability beyond criminal accountability and towards more holistic accountability and justice which supports women’s economic, social, and cultural rights.

Human Rights

Nearly 22 %of Member States mentioned the human rights of individuals affected by SVIC. The Republic of Korea referred to UNSCR 1325 as “fundamentally a human rights mandate”, while Australia, Canada underlined SRHR (and lack of consensus on its reference in the Resolution) as essential to women’s human rights. Switzerland stated that SVIC cannot be addressed without inclusion of protection of human rights defenders and rights and needs of all survivors at the center of response, with Mexico, Kenya, Liberia and others echoing that protection and respect of human rights required for prevention of SGBV and protection of women.

Peacekeeping

Those states with high percentages of contribution to the UN peacekeeping forces highlighted their efforts to increase or meet the required percentages of women in leadership roles. (UAE, Bangladesh, Pakistan). While gender parity is an important objective, holistic implementation of the WPS Agenda requires going beyond adding women to promoting a gender equality and peace agenda that addresses root causes of conflict.

Justice

SRSG Patten reminded the Council that the implementation of resolutions and commitments under the WPS agenda has been slow, with access to justice and accountability elusive. Over 87% of Member States called for accountability measures to be taken to bring perpetrators of SVIC to justice. 74 States and State groupings supported the language on accountability, including sanctions against perpetrators. Germany called for strengthening of accountability, for those actors in noncompliance to be dealt with through targeted sanctions and criminal prosecution. Kuwait pointed out that in the absence of accountability, conflicts can go on longer, and limit refugees and internally displaced people from returning home in a safe and dignified manner. In a similar vein, South Africa stressed the importance of accountability in containing and ending SVIC, characterizing it to be at the heart of their action on the matter. Member States called for stronger rule of law and increased security sector reform to further bolster efforts on ending impunity for perpetrators. Throughout the debate, various Member States recognized or called on civil society to play a role in bringing about results on SVIC in the context of both accountability and survivor-centred provision of services.

International Criminal Court (ICC)

Over fifteen Member States and the EU remarked on their support and acknowledgement of the important and complementary role of the ICC and other other investigative mechanisms in addressing accountability for perpetrators. Some called on all Member States to ratify the Rome Statute of the ICC and ensure that national laws incorporate SVIC crimes. Others expressed that the work of Security Council can benefit from more systematic involvement with ICC and when national and international courts are able to act, they should create fact-finding missions to ensure preservation of evidence; and when states are unable or unwilling to prosecute, there must be the option to directly go to the ICC.

As the briefers Inas Miloud and Nadia Murad pointed out, it cannot be that civil society, survivors, and experts come to inform the Council on horrific crimes against humanity, such as SVIC, and Member Stats pass resolutions, make statements, hold conferences, and go on about business as usual. Despite being responsible for international peace and security, the Security Council has not delivered for women on issues of peace and security. Fundamentally, peace and security are inextricably linked to the respect and protection of human rights of all people. Consequently, realising the Women, Peace and Security Agenda requires an increased role and action by human rights institutions and member states to address root causes, including gender inequality and discrimination which denies women, LGBTQI, indigenous, and other populations their human rights to economic, social, political, and civil rights.

GAPS

At this year’s Open Debate on Sexual Violence in Conflict, as in years prior, there were several missed opportunities, most especially with regard to disarmament and the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons, and in the violence against women human rights defenders and human rights defenders.

Violence against Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs)

While the Resolution fails to call out the violence against women human rights defenders, the Secretary-General’s report mentions WHRDs in context of sexual violence related to political and election-related violence, and the the use of sexual violence to threaten or harm political opponents, family members and women human rights defenders. Out of 84 Member States and related state groupings, 10% of Member States and Regional Groups gave passing nods to the work of women human rights defenders. However, only Switzerland called out the violence against WHRDs committed before, during or after conflict. In her briefing Inas Miloud shared with Council that attacks against WHRDs in Libya “remain on the rise[...]Reprisals for our activism and criminalization of our work has led to severe restrictions on freedom of movement, assembly, and speech.” In his most recent report to the Human Rights Council, Michel Forst, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, highlighted the dire nature of violence facing WHRDs, including “misogynistic, sexist and homophobic speech by prominent political leaders, as well as the normalising of violence against women and gender non-conforming people”. Mr. Forst has made several recommendations to States to act on behalf of women human rights defenders by taking a public stand against all State and non-State actors who violate the rights of women human right defenders. However, only a handful of statements, by Australia, Canada, Lebanon, Poland, and the European Union commended the contributions and participation of WHRDs or human rights defenders (HRDs), and these did not acknowledge the violence they face in their borders or around the world. Failing to acknowledge the violence faced by WHRDs and HRDs in the context of conflict, before, during, and after is a continuing failure of Member States to support the social, civil and political rights of defenders, who are defending the rights of their communities for land, water, indigenous heritage and practices, or access to civil, political, economic, and social rights.

Disarmament

As WILPF’s analysis has shown, militarisation -- particularly the proliferation of weapons -- fuels sexual violence and conflict and increased expenditure on weapons diverts funding from those conflict prevention mechanisms and community-building programmes that are, ultimately, the only way to eradicate sexual violence and achieve sustainable peace. The Secretary-General’s report recommends that States strengthen prevention in the context of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programmes by integration of a “gender analysis and training into national disarmament, demobilization and reintegration processes, including resocialization and reintegration initiatives to mitigate the threat of sexual violence”. Echoing the report, Resolution 2467 also presses for women’s full and effective participation and protection in disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programs, security sector reforms, among other spaces. Yet the open debate was marked by minimal discussion of disarmament (5% of Member States’ and Regional Groups’ statements) and the illicit trade of small arms and light weapons (4% of Member States’ and Regional Groups’ statements). Estonia (speaking on behalf of itself as well as Latvia and Lithuania) stood alone in its specific recognition of the arms trade treaty as a critical contribution to efforts to eradicate sexual violence in conflict. Some Member States called out the tendency of other Member States who are involved in the global arms trade by building and selling weapons and supplying regions that are rife with violence or instability to seriously consider their words and actions. Surprisingly, in a debate where multiple States underlined the linkages between sexual violence in conflict and armed parties, there was little mention of the Arms Trade Treaty, which includes a gender based violence criterion obligating member states not to transfer arms which could be used to commit gender based violence. Only Estonia underscored the role of the ATT as critical to efforts when addressing SVIC, and the need for political will to address SVIC from this lens.